Paul Weimer recently asked:

“I saw JJ’s comment above about Space Opera and wonder just how much space is required to make a Space Opera a Space Opera, as opposed to being something more akin to Planetary Romance.”

It’s an interesting question that prompted responses on File 770, Cora Buhlert’s blog, and no doubt elsewhere. There probably is no hard line between Space Opera and Planetary Romance; that does not mean we cannot argue incessantly discuss passionately where the line should be drawn. Here’s my two cents (rounded up to a nickel because Canada phased pennies out in 2013)…

One world is not enough (probably). There are space operas that center on one world—novels such as Dune or The Snow Queen come to mind—but their plots require interactions between that planet and the rest of the narrative universe. The story may take place on one world, but this world is only one of many.

Space travel is a therefore a necessary feature of space opera. Travel can delightfully complicate the plot: trade, migration, proselytization, and the chance that the local equivalent of the Yekhe Khagan might pop by with ten thousand of his closest friends to discuss taxation and governance.

We also expect a setting that suggests great expanses of space and time. Opera, after all, often involves spectacle, and what grander scale than a million worlds? Or distances so vast that entire species have gone extinct while light was crawling across interstellar gulfs?

All of which seems to imply that space opera requires interstellar travel and a galactic setting. But…but… let us not get ahead of ourselves.

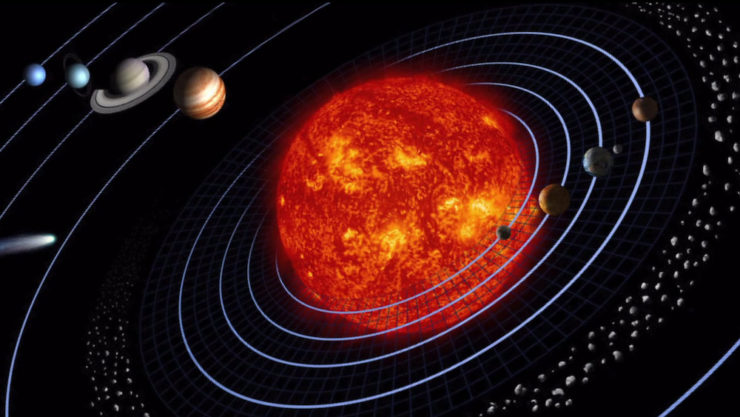

First of all, if the author limits themself to plausible or semi-plausible propulsion systems, the time required to traverse the Solar System will expand immensely. Second, the Solar System is actually quite, quite large. A combination of

- realistic delta-v (kilometers or tens of kilometers per second)

- or possibly higher delta-vs (at the cost of hilariously low accelerations)

- and great solar distances

can imbue a tale with the scale and grandeur we usually associate with galactic space operas.

The same advanced technology that can deliver a warhead full of nuclear awesomeness from a Russian missile silo to your living room in less time than it takes to watch an episode of Game of Thrones would take half a week to reach the Moon. And nine months to reach Mars. Or consider the reach of electromagnetic radiation (which includes light). The signals that can circle the Earth in a seventh of a second would take almost a second and a third to reach the Moon, more than three minutes to reach Mars, and over half an hour to reach Jupiter. The outer reaches of our solar system are even farther away. The spacecraft New Horizons is more than six hours away by photon; Voyager One is so far away that light takes seventeen hours to arrive.

Moreover, the Solar System is both very large and full of stuff. At least eight planets and five dwarf planets. Almost two hundred known moons. Maybe one hundred thousand 100 km+ Kuiper Belt Objects. Perhaps two million large asteroids. A trillion bodies in the Oort Cloud. Assuming sufficiently advanced life support, time, and some reason to plant people on various celestial bodies, there’s certainly room for as many distinct cultures as any galactic space opera offers.

Eleanor Lutz’s Asteroid Map of the Solar system gives a nice impression of what’s out there just in the Inner System (and is available for purchase in a variety of formats.)

Even better, the distribution of matter in the Solar System lends itself to plot-enabling complications.

Contrary to the old belief that spacers would avoid large masses, it turns out that planets (Jupiter in particular) are extremely useful sources of free momentum (spacecraft can swing round those worlds for an extra boost). Well, free at the current moment. Anyone who can control access to Jupiter may be able to make a nice living off that control. How to establish control? How to maintain control? There are stories in those questions.

Then there’s the fact that the distances between objects in the Solar System are dynamic. Here, enjoy this animation of the orbits of Jupiter’s Trojans:

Human colonies may alternate between glorious isolation and easy access to other colonies . This would be predictable (orbital mechanics for the win), but it would still make for some interesting politics and would complicate trade in interesting ways . Poul Anderson wrote a story based on this observation (“The Makeshift Rocket”); I am sure that other stories are possible.

Once one is past the Belt, each planet’s satellite system presents the potential for a natural community, close to each other both in terms of time and delta-v. As pointed out decades ago in “Those Pesky Belters and Their Torchships,” this means one could have a setting in which the Solar System might be divided into dozens of nations, which as we all know from current history, is a very plot-friendly arrangement.

Scale, plot-friendly orbital dynamics, plot-friendly heterogeneous matter distribution: the Solar System all by itself provides every resource a space opera author could want.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.